This post is lengthy but it reviews the history of capital punishment in the US. All of the following 8 posts on the next 8 Sundays will deal with the heart of the matter: the bias created in selecting a capital jury.

In 1968, the Court, in Witherspoon v. Illinois,8 looked at an Illinois statute which stated, in a capital murder trial, a juror will be excused for cause upon a finding that “he has conscientious scruples against capital punishment, or that he is opposed to the same.”9 This statute essentially allowed the prosecution to remove, for cause, any juror that was opposed to capital punishment, regardless of whether the juror would be able to put their beliefs aside and still apply the evidence to the law. “But when it swept from the jury all who expressed conscientious or religious scruples against capital punishment and all who opposed it in principle, the State crossed the line of neutrality. In its quest for a jury capable of imposing the death penalty, the State produced a jury uncommonly willing to condemn a man to die.”10

The Court in Witherspoon concluded that “a sentence of death cannot be carried out if the jury that imposed or recommended it was chosen by excluding veniremen for cause simply because they voiced general objections to the death penalty or expressed conscientious or religious scruples against its infliction.”11 This holding makes clear that any person excused because he or she would automatically vote against the death penalty, regardless of the evidence, and anyone who could not be impartial during a determination of guilt because of his or her views on capital punishment, may be excused from the jury for cause.12 The first prong of the Witherspoon test would eliminate all of those whose beliefs regarding the death penalty would not allow them to vote for death during the penalty phase, regardless of the evidence presented. The second prong would eliminate all of those whose beliefs regarding the death penalty would make it difficult for them to vote for the defendant’s guilt during the guilt phase of the trial. In 1968, the Court held that these two types of “Witherspoon excludables” are constitutionally valid.13

“The most that can be demanded of a venireman in this regard is that he be willing to consider all of the penalties provided by state law, and that he not be irrevocably committed, before the trial has begun, to vote against the penalty of death regardless of the facts and circumstances that might emerge in the course of the proceedings. If the voir dire testimony in a given case indicates that veniremen were excluded on any broader basis than this, the death sentence cannot be carried out…

We repeat, however, that nothing we say today bears upon the power of a State to execute a defendant sentenced to death by a jury from which the only veniremen who were in fact excluded for cause were those who made unmistakably clear (1) that they would automatically vote against the imposition of capital punishment without regard to any evidence that might be developed at the trial of the case before them, or (2) that their attitude toward the death penalty would prevent them from making an impartial decision as to the defendant’s guilt.”14

Essentially, what the Court in Witherspoon allowed is for all open minded people to be death qualified. A juror would be qualified to serve on a capital jury so long as his or her beliefs for or against the death penalty would not cloud his or her judgment in rendering a verdict and, possibly, a sentence. This created a more neutral jury, though still slanted against the defendant. Witherspoon allowed for individuals to be death qualified if they could be open minded and apply the law if the evidence showed the defendant was guilty and deserved of a death sentence, regardless of his or her specific beliefs on capital punishment. Any person who would be unable to vote for a verdict of guilt or for a sentence of death because of his or her beliefs on capital punishment, would be excused for cause.15 However, a person who voices general concerns about the death penalty but makes clear that he or she would be able to remain unbiased and render a verdict of guilt or sentence of death, may sit on a death qualified jury.16 Nevertheless, the prosecution would most likely be unwilling to make a gamble and place someone like this on a jury, so, in all practicality, he or she would most likely be excused peremptorily.

In 1971, the Court held that it was not a violation of the Constitution to leave the sentencing decision to the jury.17 “In light of history, experience, and the present limitations of human knowledge, we find it quite impossible to say that committing to the untrammeled discretion of the jury the power to pronounce life or death in capital cases is offensive to anything in the Constitution.”18 The Court held here that a single jury could be used for both the guilt phase and penalty phase of a capital trial.19

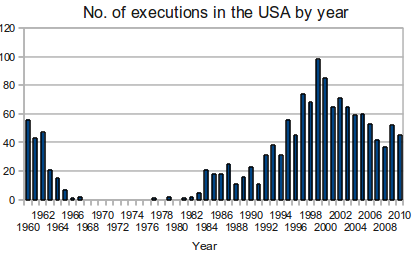

In 1972, the Court dealt proponents of capital punishment a blow when it brought an end to capital punishment in the United States.20 The argument in Furman was that capital punishment was a violation of a person’s right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment as provided in the Eighth Amendment.21 In Furman, the Court held that the current procedures used by the states in handing out death sentences were objectionable.22 Thus, the states were free to reestablish capital punishment but were required to come up with a new way to implement the penalty.23

The State of North Carolina interpreted Furman to allow mandatory death sentences for first degree murder. In 1976, the Court considered the Constitutionality of that scheme.24 The Court held this manner of utilizing capital punishment to be unconstitutional because “the practice of sentencing to death all persons convicted of a particular offense has been rejected as unduly harsh and unworkably rigid.”25 Additionally, the mandatory sentencing scheme failed to address the unguided and unchecked jury discretion prohibited by Furman as well as the fact that “relevant aspects of the character and record of each convicted defendant” could not be considered by the jury.26

Also in 1976, the Court considered the death penalty scheme enacted by several states which gave juries guided discretion in applying the death penalty.27 Giving a jury complete discretion regarding the application of the death penalty was held unconstitutional.28 “Furman mandates that where discretion is afforded a sentencing body on a matter so grave as to the determination of whether a human life should be taken or spared, that discretion must be suitably directed and limited so as to minimize the risk of wholly arbitrary and capricious action.”29 This guided discretion, which allows the jury to decide the sentence, but only after considering aggravating and mitigating circumstances, is a constitutionally permissible method of applying the death penalty.30 Thus, after 1976 and Gregg, capital punishment was once again a permissible penalty for crimes of murder.

In 1985, the Court decided Wainwright v. Witt.31 The Court in Witt took the two prongs from Witherspoon and created one standard. “[A] juror may not be challenged for cause based on his views about capital punishment unless those views would prevent or substantially impair the performance of his duties as a juror in accordance with his instructions and his oath.”32 The substantial impairment standard set forth in Witt is still the standard in effect today.

One year after Witt the Court decided Lockhart v. McCree.33 McCree argued that death qualification was unconstitutional because it created a more conviction prone jury.34 The Court reviewed several studies supporting McCree’s claim and stated, “we will assume for purposes of this opinion that the studies are both methodologically valid and adequate to establish that ‘death qualification’ in fact produces juries somewhat more ‘conviction-prone’ that ‘non-death-qualified’ juries.”35 Nevertheless, the Court held that death qualification was not unconstitutional.36

It has been argued that the death qualification process creates a jury that is more conviction prone than a non-death qualified jury because the jury lacks impartiality.37 The Court has held that a juror is impartial “if the juror can lay aside his impression or opinion and render a verdict based on the evidence presented in court.”38 In his case, McCree argued further that his jury lacked impartiality because, after the excludable jurors were removed, those that remained “slanted the jury in favor of conviction.”39 The Court dismissed both of these arguments holding that death qualification does not violate the fair cross section of the community requirement for a jury.40

Both Adams and Witt changed the standard set forth originally in Witherspoon by creating the merged prong of substantial impairment.41 The new test was whether a juror could follow the law if the law and evidence called for the death penalty.42 If not, the juror could be excused for cause.43 Lockhart further expanded this test by holding the “Witherspoon excludables” would now be excluded as “unable to follow the law.”44

In 2002, the Court held the execution of a mentally handicapped person was unconstitutional.45 The Court relied upon the concept of “evolving standards of decency” to determine if the execution of mentally handicapped people was cruel and unusual punishment.46

In Ring v. Arizona, which was also decided in 2002, the Court held the trial judge could not find facts beyond those found by the trial jury.47 Judges are allowed some discretion in determining the proper sentence, but a judge cannot find an aggravating circumstance in order to sentence the defendant to a more severe punishment than life imprisonment.48

In 2005, the Court held it to be unconstitutional to execute individuals who committed a capital offense prior to turning eighteen years of age.49

8 391 U.S. 510 (1968).

9 Ill. Rev. Stat., c. 38, § 743 (1959).

10 391 U.S. at 520-521.

11 Id. at 522.

12 Id.

13 Id.

14 Id. n.21.

15 Id. at 522.

16 Id.

17 McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971).

18 Id. at 207-208.

19 Id. at 209-210.

20 Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

21 Id.

22 Id.

23 Although, it is true that both Justice Marshall and Justice Brennan felt that capital punishment was always cruel and unusual punishment. For their remaining time on the bench together, they would dissent to every opinion ruling on capital punishment arguing that it violated the cruel and unusual punishment standard.

24 Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976).

25 Id.

26 Id.

27 Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976).

28 408 U.S. 238.

29 428 U.S. at 189.

30 Id.

31 469 U.S. 412 (1985).

32 Id. at 424 (quoting Adams v. Texas, 448 U.S. 38, 45 (1980)).

33 Lockhart v. McCree, 476 U.S. 162 (1986).

34 Id. at 169-170.

35 Id. at 173.

36 Id. at 177.

37 Id.

38 Irvin v. Dowd, 366 U.S. 717, 723 (1961).

39 476 U.S. at 177.

40 Id.

41 448 U.S. at 45.

42 Id.

43 Id.

44 476 U.S. at 176.

45 Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

46 Id. at 321.

47 Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584, 588 (2002).

48 Id. at 588-589.

49 Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005).

Related Posts

Latest posts by Bryan Driscoll (see all)

- Where is the Outrage from the Right? - February 19, 2017

- Eight Days - January 29, 2017

- Tomorrow - January 21, 2017

Pingback: Capital Punishment VII | 2 Rights Make a Left